Chess Set

THE “GULAG” KNIGHTS

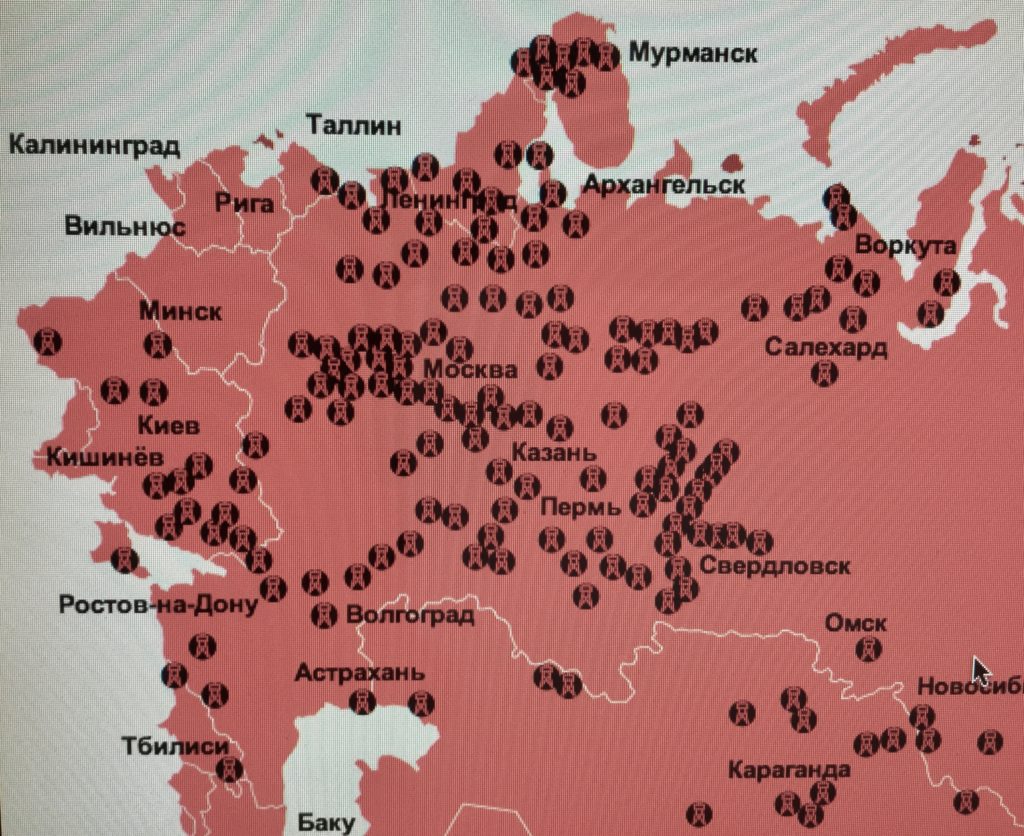

GULAG: Glavnoe Upravlenie ispravitenie-trudovykh LAGere (Chief Directorate of Corrective Labour Camps); A prison system based on forced manual labour. It was established under the rule of Lenin and peaked during the Stalin era. The last of 476 Russian gulags (Camp Perm-36, Solovki) was closed in 1987. Vladimir Petrov, mentioned below, died in a coal-mining gulag located just outside of the Arctic Circle at Vorkuta in 1943. Carving chess knights, in comparison, must have seemed like a luxury.

Collecting vintage Soviet chess sets has become quite popular of late, especially over the last ten years or so, as more and more Russian dealers have taken to selling their wares through online auction houses and e-commerce websites such as ebay, shopify and etsy. Most of these sets, and by far the most numerous and affordable examples date from the period ranging from just before the USSR’s Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945 up to the introduction of plastic pieces during the 1960s eliminating the need for wood-carvers, or the so-called ‘Carpentry Brigade’ of the Russian gulags, of which we will speak more of later.

Needless to say, there had always been many thousands of chess sets in Russia prior to the turn of the twentieth century, thanks mainly to the popular figures of Petrov, Jaenisch and Chigorin, the founding fathers of The Soviet School of Chess that peaked during the 1960s when household names such as Botvinnik, Smyslov, and the Latvian ‘Magician’ Tal would

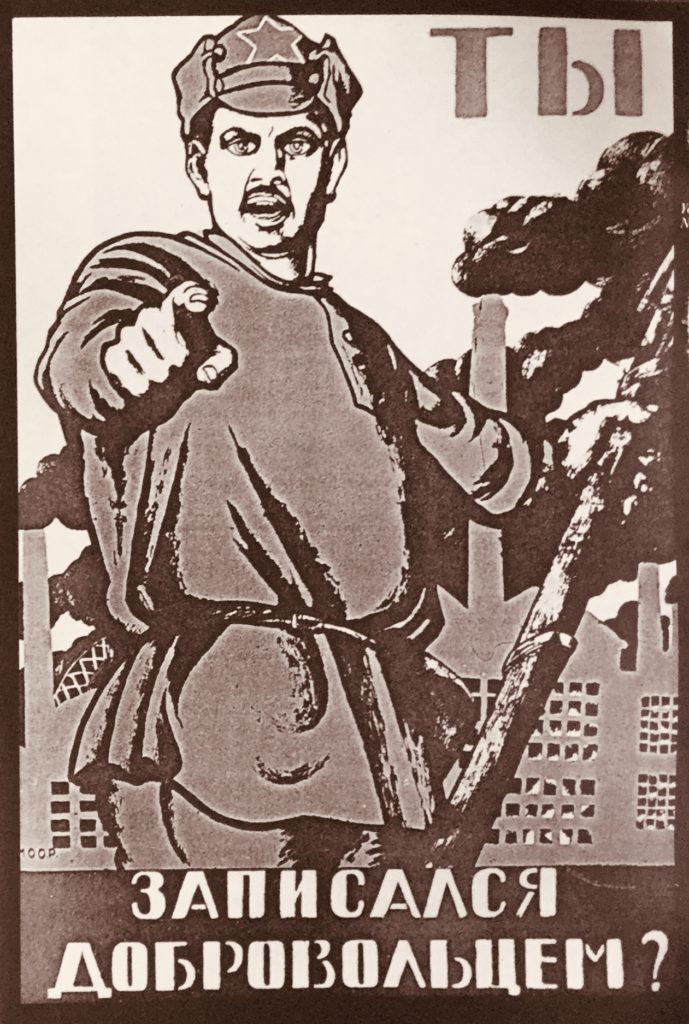

dominate world chess. However, it wouldn’t be until after the establishment of the USSR in 1922 that we see a concerted effort by the ruling parties, particularly under the guidance of Nikolai Krylenko, Stalin’s right-hand-man and Chairman of the Chess Section of the Supreme Council for Physical Culture of the Russian Federal Republic (whew!), who championed the game of chess as “…not an end in itself, but a means of raising the cultural (and thereby also the political) level of the laboring masses,” 1The Kings of Chess, Ch. 11, ‘The Russians Are Coming’ (Hartford, 1985) p.125 In other words, a relatively inexpensive esoteric tool to help occupy the minds of a mainly illiterate (and mostly drunken) workforce with the ultimate aim of placing a Russian foot firmly onto the world stage in the decades to come – a goal Krylenko ultimately achieved in typical Soviet style under the catchy red banners; “Chess for the Workers!” and “Your Chess Club Needs You!” – accompanied by the rather droll (one of Stalin’s probably?), “Chess is an Instrument for the Cultural Advancement of the Masses.”2The Soviet School of Chess, Kotov/Yudovich, 1958. p54 And who would argue with Stalin!

The turning point for this goal was the year of 1917 giving rise to the Great October Socialist Revolution. Prior to this, the country had been pinned under the thumb of a struggling and completely disjointed Romanov dynasty that had grasped onto power for over 300 years. During this era Russia had all but stagnated compared to the rest of Europe gaining a reputation in the newly industrialized Great Britain as being “somewhat of a backwater country,” a “throwback to medieval times” even,3Empire of the Tsars (Ep. II, BBC documentary, 2016)

as very little had changed as far as the serfs – the long-suffering peasant work-force – were concerned since the coronation of the first Romanov, Peter the Great, during the latter part of the eighteenth century.

As mentioned, there were many wonderful chess sets in circulation prior to 1917, variably made of ivory, precious metals, exotic woods and ceramic, the creations of skilled craftsmen called Shakhmatniks (chess-makers) who worked almost exclusively for the Romanov’s and other top-draw nobility. Sadly, many of these ‘dream’ collector’s sets were either lost or destroyed during the October Revolution when even singing and joking was “highly discouraged” and to partake in an esoteric game of chess was condemned by the new Bolshevik regime as a “decadent bourgeois pastime” bringing an abrupt end to “virtually all organized chess activities in Russia.” 4Russian Chess History: B. Wall, chess.com June 2008 For this reason the English master, Harry Golombek, in his History of Chess (London 1976) skips this period altogether and focuses instead on the years between 1938 and 1963, a period of “intensive activity” (as he observed) in an era “of mass production,” both of Soviet chess-sets and Soviet chess-players alike. And likewise, we will focus on the thirty years between 1945 and 1975, when the ‘mass production’ of chess sets in the Gulag factories and the rise of the Soviet School of Chess marched hand-in-hand, eventually winding their way to Reykjavik, Iceland for a showdown with the infamous American, Robert ‘Bobby’ Fischer, in 1972 (the subject of a future discussion).

Firstly, however, let me quickly throw a few numbers your way, just to better understand the extent of Stalin’s massive Gulag system that stretched from St. Petersburg to the Arctic Circle and down to Vladivostok near the Chinese/Korean border. Between the years of 1930 5The camps were officially established on April 25th 1930 to coincide with Stalin’s ‘Industrialization Campaign’ and were each assigned a distinct economic task that ranged from mining of nickel, tin, iron-ore, silver and gold, woodworking (deforestation, carpentry, etc.), construction work and the manufacture of arms and artillery, etc.and what became known as Khrushchev’s Thaw in 1954 (when the Gulag system was revised and 4 million sentences were reviewed), an estimated 18 million people were processed through the forced-labour camps scattered throughout the Union.

This figure does not include the intelligentsia, or political prisoners, which at the time of Stalin’s death in 1953 numbered close to 500,000. Even these numbers are mere ‘guesstimates,’ the educated guesses of modern historians (who just recently have been given access to long-buried documentation) and doesn’t take into account those citizens who simply ‘disappeared’ off the radar leaving no official paper-trail – for example, the Levashenskoye Cemetery alone, near St. Petersburg, holds the bodies of about 50,000 unidentified people shot by the NKVD (precursor to the KGB) between 1937 and 1953 who were secretly buried there. 6The Moscow Times, Sept. 7th, 2010; Modernizing Russia’s Tragic History, V. Ryzhkov All very depressing reading and sadly this was not an isolated case.

Ironically, at the same time as this harrowing combination of mass-incarceration and senseless annihilation was occurring, under the guidance of Krylenko, now General Secretary of the Soviet Chess Federation, the game of chess was slowly beginning to thrive. In 1920, during a time of civil unrest and general upheaval, the very first ‘All-Russian’ Chess Olympiad was held in Moscow, and perhaps unsurprisingly, it only mustered a handful of entrants from the heavily scrutinized 1000+ members of the Russian Chess Association including one sole grandmaster (Alekhine) and just three other masters. In comparison, ten years later there were over 150,000 registered players, and by 1965 the Soviet Union could boast of four past World Champions and one current World Champion (Petrosian) with over 3.5 million officially registered FIDE players. Quite staggering progress really! And long before the advent of computers all of these budding masters needed one essential tool – a chess set and board.

Needless to say, the hundreds of thousands of prisoners snatched up by the Gulag could produce hundreds of thousands of chess sets, and that’s exactly what Stalin had them do. There were two main factories (or camps) that concern this brief discussion. The first “Village” (a polite Stalinist term for a penal colony) was located halfway between the main artery connecting St. Petersburg and Moscow, namely, The Valdai Regional Industrial Manufactory in Novgorod (450 km north-west of Moscow), a picturesque and densely forested area used today by the rich and famous (including Putin and his entourage) for quick summer getaways. The second ‘village’ is the Yavas Township located in the Central Volga Region of Mordovia (500km south-east of Moscow), which operated from 1931-1948 for “the creation of woodworking production,” or more specifically, the manufacture of chessmen and chessboards and other (less useful) wooden products, such as tables and chairs, storage boxes, tools and everyday utensils. From these two camps came the so-called ‘Valdayski’ and Mordovian (f.k.a. “the Latvian”) sets respectively, the latter once erroneously attributed to be a “favourite” of Tal, the aforementioned ‘Magician’ of Riga.

The trademark ‘elbow’ shaped knights with their minimalist facial features is what distinguishes this set from other contemporary examples which all gained in popularity after Tal won the title of World Champion in 1960 famously defeating his fellow Russian, Mikhail Botvinnik, with a score of 6 wins, 13 draws, and 2 losses.

Photo credit: Chuck Grau Collection

It was Alan Dewey, the well-known chess-set restorer, who first referred to what we now call Mordovian knights as “Gulag knights.” “The other Alan” nonchalantly recalled in a chess.com forum in 2014 that “political exiles in Siberia” were required to carve “500 knights’ heads a day” in the Gulags, and if so, even at a very pacey rate of 30 minutes per knight, over a 12 hour ‘work day’ this would undoubtedly have required a whirlwind brigade of wood-whittlers!

Nevertheless, it is most often than not these ungainly ‘Gulag knights’ that first catch the eye. Indeed, the first ‘Valdai’ set I purchased was bought purely for aesthetic reasons, as the crudely cut knights, like the overall design, struck me as being so archetypically Russian with their large and solid ‘bell-bottomed’ bases (compensating for the lack of lead during WWII), an awkward-looking ‘pin-headed’ bishop and that curiously shaped ‘badger-like’ muzzle of the knight, which at first sight reminded me of the comical (and conical) puppets from that 70’s British kids’ show, The Clangers! – a pet name I still use for these ‘Clanger’ sets to this day.

Much like the Valdei chessmen, the Mordovian sets were also mass-produced during the 1950s running well into the late 1970s, mainly at the Yavas camp, formerly known as Temlag (a juvenile colony) and later Dubravlag (Gulag ‘special camp’ No.3), when the children’s camp was merged in 1948 with another ‘village’ of intelligentsia or political prisoners; the doctors, teachers, scientists and even non-conformist chess-players who wouldn’t dial into the party line. It is difficult, if not impossible from a historical point of view to discern whether the children of Gulag No.3 formed any part of the so-called ‘Carpentry Brigade.’ If at all, they may have been involved in the painting and shellacking process rather than mastering the more difficult skill sets of wood-turning and carving – and having handled 100’s of sloppily finished and heavily layered Soviet pieces from this era I must say, in many respects, this does look like the work of very bored children! Some say this is part of the charm of these old pieces, but as future articles will prove, I beg to differ in a high percentage of cases. But that’s a discussion for another date.

So to cap off a lengthier than planned ‘blogski’ (can I hear the retort, ‘sloggski, more like?’), the truth of the matter is, that if you have ever been fortunate enough to have handled any of these Soviet sets you’ve most certainly held the very same pieces as the unfortunate children and men of Stalin’s infamous Gulag camps, and therefore held a small wooden piece of human history in your hands – as tragic as that history may unfortunately be.

Thank you for listening. Until next time – check you later!

- The Kings of Chess, Ch. 11, ‘The Russians Are Coming’ (Hartford, 1985) p.125

- The Soviet School of Chess, Kotov/Yudovich, 1958. p54

- Empire of the Tsars (Ep. II, BBC documentary, 2016)

- Russian Chess History: B. Wall, chess.com June 2008

- The camps were officially established on April 25th 1930 to coincide with Stalin’s ‘Industrialization Campaign’ and were each assigned a distinct economic task that ranged from mining of nickel, tin, iron-ore, silver and gold, woodworking (deforestation, carpentry, etc.), construction work and the manufacture of arms and artillery, etc.

- The Moscow Times, Sept. 7th, 2010; Modernizing Russia’s Tragic History, V. Ryzhkov

Copyright Alan W. Power, Aug/Sept 2019. All rights reserved.

Originally published November 2019.

Revised October 2022 in collaboration with Chuck Grau and the members of Shakhnatnyye Kollektisionery; Soviet and Tsarist Chess sets and The Chess Schach

Fascinating.

Very interesting. I have a Soviet era set and I had no idea they were made in gulags. It changes my perspective.

Where can I acquire a Gulag chess set with the elbow shaped horses?

Hello Lawrence, I will be listing a very collectible earlier version of the ‘ Tal/Latvian’ set over Easter. Keep your eye on the GALLERY. I also have two sets ready to go in the studio, which will be listed in the next few months.

Thank you for your interest!

Best regards,

Alan

Pingback: THE GULAG ‘KNIGHT’ OF MORDOVSKA (ADDENDUM) - "For a reader living in the free world the word “thief” perhaps sounds like a reproach? But you misunderstand the term. In the underworld - The Chess Schach

Thanks for the research. I have a good example of a later gulag set, that I have weighted and felted. I disagree with your description of the knights as awkward, the bishops pin-headed, and the carvings crude: I find the pieces graceful, particularly compared with the more blocky Staunton type. With weight added, they fit the hand nicely and the wide bases make them unusually stable, The added poignancy of this horrific history deepens the chess experience.