Chess Set

‘TRIPPING’ THE MEDIEVAL FANTASTICUM

For the February Chessay I offer the following snippet from a side-project I have been working on for the past ten years or so – TEN YEARS OR SO! Where does the time go? I very much doubt that it will ever get finished, but taking a leaf out of the book of the great Charles Dickens, I venture to do the same here and present the reader with a few short instalments. And who knows, maybe some of you ‘Chessayers’ may like what you read and I may be inspired to dedicate a little more time to finishing the project in the future. Who knows? In any case, here goes, I’ll play my gambit…

The work is tentatively titled THE INGLORIOUS GAMBITEERS – A HISTORY OF THE GAMBIT (1475-1925) and delves into the origins of the Modern English word ‘gambit’ following its etymological history throughout the ages and eventually leading into the games of the early pioneers of these swash-buckling openings (Lopez, Ponziani, Greco) who used the “gambett game” (Middle English) so successfully during their era and inevitably inspired the likes of more modern gambiteers such as the Russian champion Chigorin, the cunning “swindler” Marshall and the quiet assassin, Spielmann. Hopefully, it should be a mildly entertaining and informative ‘trip’ or dance through the centuries (containing a fair amount of chortle-worthy ‘medieval slang” you may be warned!) and also takes a pop at the Oxford English Dictionary‘s slightly dated etymology of the term ‘gambit,’ first defined in the 1920s by the grandmaster of British chess historians and meticulous lexicographer, Harold J. Murray. Needless to say, a hard man to mince words with! But bear with me if you will over the following weeks as we drift back and forth in time to truly understand the ‘exact’ meaning of the term ‘gambit’ that eventually carries us back to the days of William the Bastard, the Norman ‘Conqueror’ of England in 1066!

The first chapter is named THE SPANISH INQUISITION – and I hope it isn’t torturous! There are eight further sections listed below, not too lengthy. If there’s enough interest I’ll continue posting further instalments every few weeks or so on a Sunday morning. It’s an interesting yarn once it gets going and should go well with a nice cup of tea and a few digestives … bacon, eggs … toast and marmite …

To tempt your palate further, the future segments are teasingly titled;

- El Ascendencia del Gambito

- Los Reyes Catolicos

- Joch de Nou

- Eloquentissimus

- Salutem Plurimam Dicit

- Dare le Pedone

- Origine Imperiale

- Gomito di Damiano

THE SPANISH INQUISITION: CHAPTER ONE

Our camino begins – as we will be pursuing an ancient and somewhat unexplored ‘trail’ of sorts – at la Ciudad Dorada, the ‘Golden City’ of Salamanca, where in 1243, El Santo, or Saint Ferdinand III, the forty-four-year-old linchpin of Spain’s volatile northern kingdoms of Castile and León, followed through on a cultural initiative instigated by his late father, King Alfonso IX, in establishing at the old Roman trading post a “Studium generale” (a school of higher learning) seeking to emulate and outshine those more entrenched seats of education already founded at Bologna, Paris and Oxford. For it was here, somewhere beneath the Universidad de Salamanca’s glistening sandstone cloisters that an ambitious young letrado, who simply signs himself Lucena – just one of a thousand faceless students of Castilian civil law – nurtured an idea for the first practical treatise on what is now commonly referred to as the ‘modern game’ of chess.

Inspired perhaps by the erudite atmosphere of his venerable surroundings (or quite simply by the fiery passions of youth?) this handsomely finished volume, bound in lavish red morocco leather with gilt-edged vellum leaves, bore the curious title of Repeticion de Amores e Arte de Ajedres con CL Juegos de Partido (Lessons of Love and the Art of Chess with 150 Endgames) which was pressed, dried and tied during the hectic yet convivial summer months of 1497 when the city and citizenry alike were dusting themselves down for the much anticipated arrival of the newly-wed heir to the Spanish throne, Prince “Johan” (as our author refers to his liege), the nineteen-year-old son of Queen Isabella I ‘La Catolica’ of Castile (who we shall hear much of later), or more formally, His Most Serene Highness, Don Juan, Prince of Asturias – the most unfortunate recipient of Lucena’s obsequious dedication.

As the title suggests, the whole tractado (using the Old Castilian slango) wasn’t solely devoted to a singular subject, as only the latter and decidedly more substantial part of the ‘treatise’ was dedicated to the intricate art of chess-play, while the initial thirty-or-so pages explored the equally intrinsic art of “el juego el amor” (’the game of love’). A topic our lovesick, or most probably, publicly ‘jilted’ young scholar laments over exhaustively, chastising the “fickle” and “changeable” nature of women during the opening moves, if you will, of medieval courtship, a view Mutulka champions in An Anti-feminist Treatise of Fifteenth-Century Spain: Lucena’s Repeticion de Amores (NY 1931), as we’ll touch on shortly. Although the distinctly parallel yet discursive genres of love and chess had been a familiar metaphorical tool of court poets and satirists since the hey-day of the silver-tongued troubadours, our like-minded author, playfully dubbed “eloquentissimus” (‘the eloquent one’) by his more-famous literary colleague and fellow student, Fernando de Rojas (c.1475-d.1541), broached the two subjects by comparing the gentler sex’s intuitive “skills” at “artes el amor los engaño” (‘the deceitful tricks of love’), or more fervently, how “mala mujer” (‘wicked women’) intentionally toyed with the hearts and minds of men, against the recent meteoric rise to power of the chess-Queen. For many centuries in Moorish Spain the Alferza had been a decidedly weak piece representing the chief-whip of the Shah (our modern-day King), his trusty right-hand-man, so to speak, who never left his side, but was now suddenly thrown from his lofty position, practically overnight, and transgendrified into the decidedly more feminine – and independent! – form of a “Dama” (or ‘Lady’) as our letrado called the Queen, whom all of a sudden became the most powerful piece to ever wave her royal tootsies over the sixty-four squares!

(Above) A good effigy of Queen Isabella of Castile snapped on a recent visit to Madrid’s magnificent Royal Palace and Armoury.

Over five hundred years later and the jury is still out on whether Repeticion de Amores was truly intended as a cheeky swipe at the Dama’s recently enhanced powers, or quite simply a hastily compiled dissertation on the ‘deceptive’ manoeuvres found in both love and chess, thrown together to curry favour with His Most Serene Highness (and prospective patron?) “Johan el tercero,” as Lucena flatteringly referred to his presumptive future king – Juan III of Aragon and Castile. And likewise, the aforementioned Barbara Mutulka, a noted Iberian scholar and women’s rights activist during the 1930s, judged the offensive incunabulum to be “an exposé of anti-feminist doctrine of the period [which] reads like a medley of all the marginal notes [the writer] had ever gleaned on the subject of love’s evils” (just tell it like it is, Babs!). A view shared by another Babs! Barbara Weissberger, several decades later in her book Isabel Rules (Minnesota 2004), tarring Lucena’s little tome with a similar brush, deeming it “a distinctly tongue-in-cheek … misogynistic parody of the academic exercise of the repetitio (oration).” All leading to an expansive and diverting discussion that we shall tactfully set aside for those learned scholars of Iberian literature. For other than a few vague clues as to the author’s “unripe” and “sarcastic” humour (again, Mutulka – she obviously had no time for Lucena at all!) this provides little impact on our chosen camino. Arte de Ajedres, on the other hand, is priceless! As we are presented with a smattering of the most popular opening systems used in the last quarter of the fifteenth-century – and two of these just so happen to be very early forms of what a certain Castilian clergyman, the famed “Clerico di Zafra” – otherwise known as Ruy Lopez de Segura – would later coin a “gambito!”

EL ASCENDENCIA DEL GAMBITO

Compared to modern standards the analysis found in Arte de Ajedres may seem rather “primitive,” as the pragmatic world champion Emanual Lasker once said, but it was a beginning. The true historical value of Lucena’s treatise is that it records a period of transition in European chess that changed quite dramatically in the last quarter of the fifteenth century when the deathly slow game of the Moors, which in Lucena’s day was called “el juego viejo” or the ‘old-style of play’ was intermingled with the more dynamic play he refers to as “el juego dela Dama,” or ‘the Queen’s Game.’ A name that arose from a revolutionary new set of laws and rules proposed by a close-knit circle of very well-connected and savvy courtiers who served under Queen Isabella’s husband, King Ferdinand II of Aragon, during the early 1470s when …

… and here we’ll leave it until next time. OH! THE SUSPENSE! That is, if there is a next time – let me know! If you’re interested in pursuing our camino a simple ‘thumbs up’ will do, don’t get too excited! If not, at least it’s a nimble fortnightly workout for the fingers, which is always handy…

Appreciate the company, my friend. Until next time – check you later!

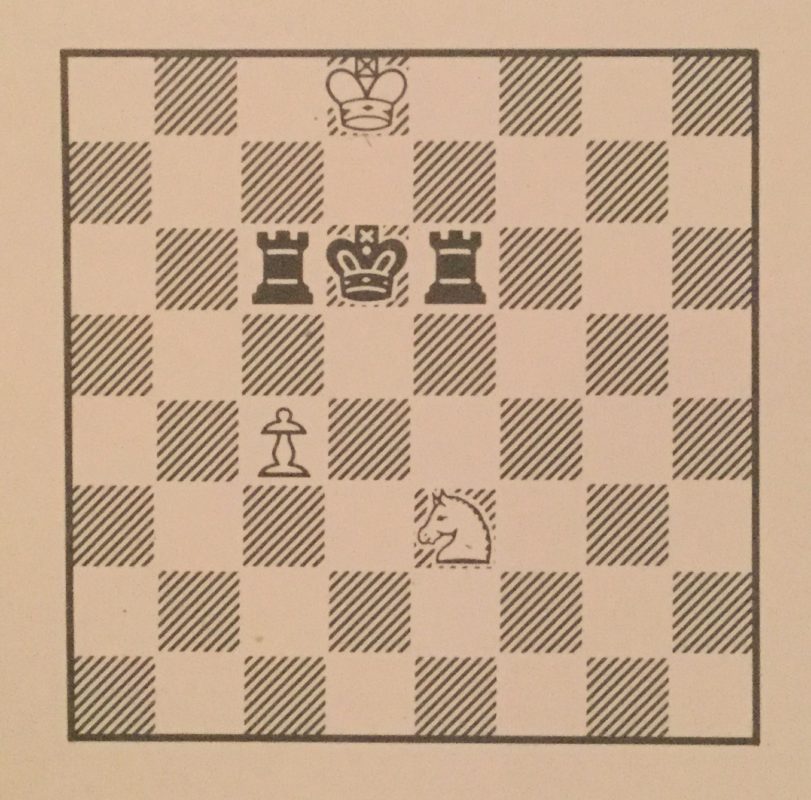

Above: Board position from my opening illustration (drawn in late 2009!), inspired by the illuminated manuscript of King Alfonso X the Wise, the wonderful Libro de Axedrez, Dados y Tablos de Alfonso X el Sabio (Book of Chess, Dice and Backgammon, Seville, circa 1280-1283).

Diagram from A History of Chess (Golombek 1976). Black to move and mate in 3. The solution, if needed, is given in the next Chessay – or can be found on p.62 of H.G.’s History.

All illustrations, photographs and text are my own (unless stated); copyright Alan Power, The Chess Schach 2020 and cannot be republished, reprinted or quoted without permission.