Chess Set

THE GULAG ‘KNIGHT’ OF MORDOVIA (ADDENDUM)

“For a reader living in the free world the word “thief” perhaps sounds like a reproach? But you misunderstand the term. In the underworld of the Gulag the word is pronounced in the same way that the word “knight” was pronounced among the nobility – and with even greater esteem, and not loudly but softly, like a sacred word. To become a knight one day … was a kid’s dream.”

Aleksanor Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago (Paris, 1974).

For the abbreviation index, please see footnote.1

Between 1950 and Stalin’s death on March 5th, 1953, the Gulag population hit its peak with just over 2,500,000 people in prison camps throughout the USSR. This is the story of just one of those prisoners, a mere ‘kid’ at the time and his cherished chess set, both of which, thankfully, survived the “purest terror.”

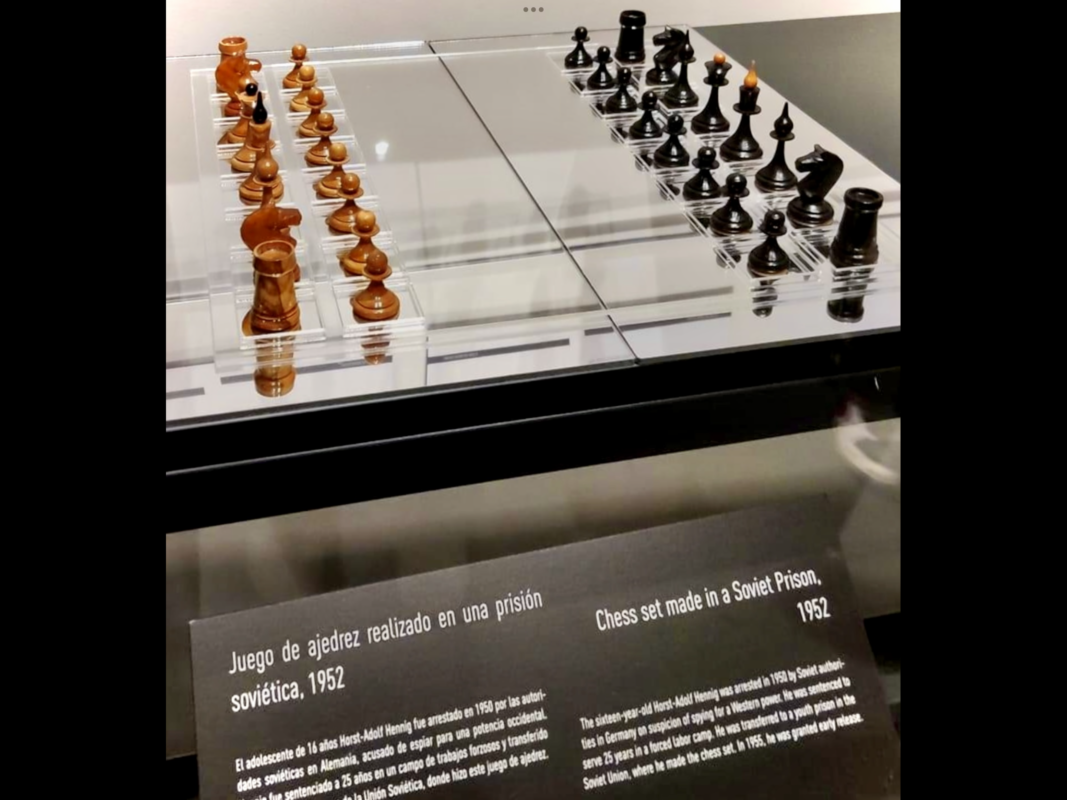

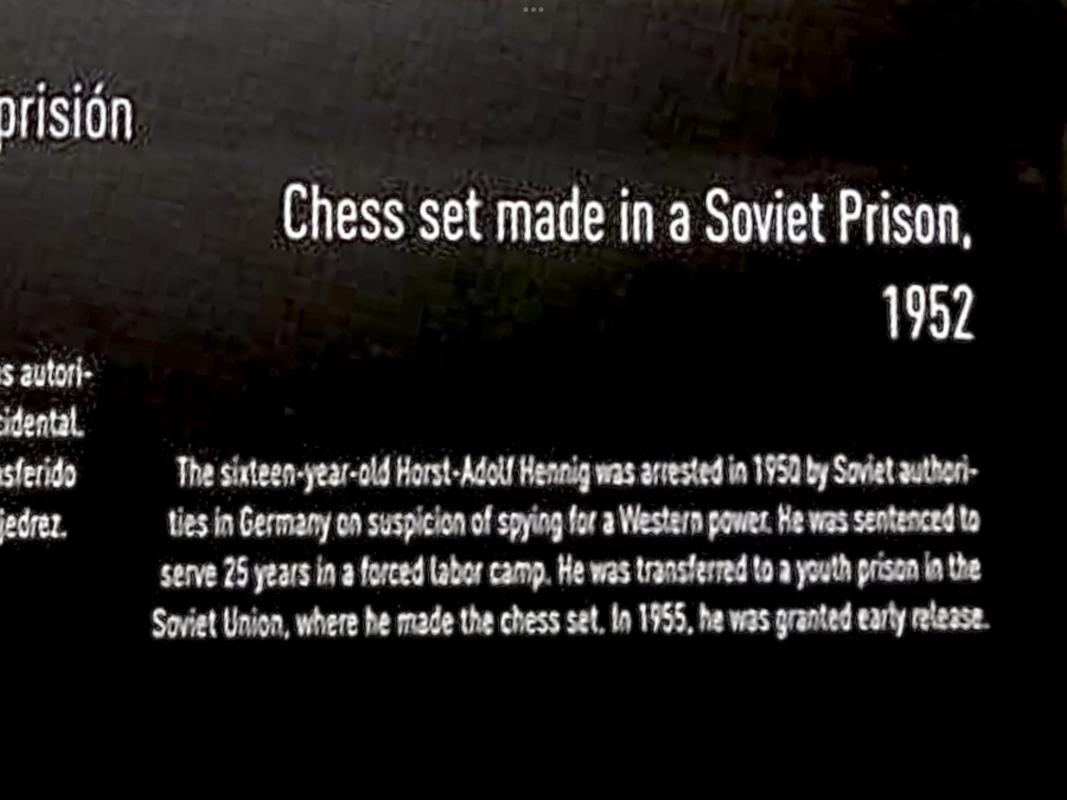

‘One thing leads to another,’ as the old saying motheringly reminds us, and a quick check through my socials one January morning proved the old dear right, as I was plunged, noggins first, back into the murky depths of the Soviet penal system and the now-iconic chess sets those unfortunate detainees distractedly lathed, carved and shellacked within their barbed-wired confines. The social trigger was a photograph taken by a chess enthusiast, Jose Manuel Astilleros, at ‘The Berlin Wall’ exhibition currently running in Madrid, Spain. Jose’s intriguing snap captured a medium-sized ‘Mordovian’ pattern made at a “youth prison in the Soviet Union” by its owner (no less!), a German chap by the name of Horst Hennig – I just needed to know more!!

In my “groundbreaking” 2019 chessay, The Gulag Knights, I left the subject open-ended with the parting observation; “It is difficult to discern whether the children of Gulag No.3 formed any part of the so-called Carpentry Brigade …” as I was unable to confirm my suspicions at the time. Five years later, through my own research and information accumulated through Chuck Grau’s illuminating SCS site, I can finally say, without doubt, that at least five carpentry brigades were making chess sets along with a young prisoner – a child of Gulag No.3 – who did indeed play a role in the production process. So grab a cuppa, kick your feet up, and let’s listen to his story…

Horst-Adolf Hennig was born on a small farm in the village of Krussau (sixty miles west of Berlin) during the spring of 1934, in what later became Soviet Occupied Germany. He idolized his papa, a decorated Luftwaffe pilot who raised his son “to be loyal to the German Fatherland” (as Horst relates in a recent podcast) and after the end of the Great War, often accompanied his father on short business trips, although it’s unclear what this ‘business’ involved. On one such trip in the early summer months of 1950 his father asked him to deliver a sealed, unmarked envelope to an address in Berlin. The youngster, who “would do anything his father asked,” complied unquestioningly, and after locating the apartment handed the missive over to an “English-speaking officer” and thought no more of it. And this is where his nightmare began.

In late July of the same year his father departed on another of these business trips, but this time he didn’t return. A few days later, the family home and outbuildings were searched and torn apart “by Russian soldiers with bayonets” (most likely MVD). Horst described the following months as “a period of angst and uncertainty” (no kidding!), then in November his mother was arrested, and in a deft pincer movement, the sixteen-year-old schoolboy was uprooted from his lessons by two “German men in plain clothes,” frog-marched from the school building and shoved into an awaiting military vehicle “with Russian license plates.” His protests; “Why? What for? I’ve done nothing!” fell on deaf ears. There was only one question; “Tell us, are you a spy like your father?” As you may have guessed, the Berlin apartment was a foxhole of the KgU, or Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit, a militant, anti-communist organization backed by Truman’s CIA.

RATHENOW PRISON, BRANDENBURG / CHRISTMAS, 1950

Young Horst would never see his father again. The teenager was tossed into solitary at nearby Rathenow Prison where he was mentally tortured, deprived of water, half-starved (fed only salzhering – dried brined herring “causing an insane thirst.”) and interrogated relentlessly, including Christmas Day and Boxing Day, “when a prisoner is at their lowest ebb.”

Still maintaining his innocence, in the third week of January he was transferred to Potsdam Prison run by the MVD, at the prison gates the escorting guard put a pistol to his head and whispered “du kaputt,” and he truly believed he’d been sent there to die.

I’ll refrain from delving into the harrowing details of his time at Potsdam, suffice to say, the experience had a lasting effect on his long-term mental health, as he discussed in a 2017 interview with historian, Dr. Meinhard Stark for the Gulag Contemporary Witnesses podcast. I transcribed the German manuscript from Hennig’s interview for use in this chessay, and it wasn’t a comfortable read. Still, in many respects, the base inhumanness of these interrogations must have prepared the young man – mentally, if not physically – for the “purest terror” that unbeknownst to him loomed just around the corner.

In February 1951, in a Potsdam military court, the sixteen-year-old Horst Hennig, barely able to stand, was handed the quarter, a sentence of 25 years of forced labour for espionage and counter-revolutionary activities. His mother received 15 years of forced labour, his beloved father was shot. After what must have seemed like a surreal week in rehab following the interrogations and trial (he ate regular meals and “slept in a bed with clean white sheets”) Horst was transported to the Potsdam train station and handed a one-way ticket to Gulag. There he was loaded onto the dreaded cattle-wagons (called the red cows) along with countless other miserable souls sentenced to a tenner or a quarter “for taking a stalk of grain, a cucumber, a chip of wood or a spool of thread.” And as the elderly survivor lamented, “…and so began my ‘Odyssee’ amongst the juvenile offenders (‘den jugenlichen krimmellen’) … known only as number 2-348.”

TEMLAG CORRECTIVE & INDUSTRIAL CAMPS / YAVAS VILLAGE (ITL ZhKh-385), MORDOVIA

POTMA, GULAG No.18 (ZhKh-385/18) / Transit Prison, March 1951

2-348’s introduction to Temlag began at Potma Prison, Mordovia, with a strip search, a savagely shaved head and (as he manages to quip) “new worn-out Russian clothes” made from “the usual dark blue cloth” (i.e. the gulag suit, or prison uniform). Interestingly, this traditional “dark blue cloth” is very similar to the cloth base pads found on many Mordovian sets of this era.

And as the Soviets never let anything – anything at all! – go to waste, it stands to reason that these useful prison off-cuts (including other materials, too) may have been ‘repurposed’ for use on the chess pieces. After all, we already know that the repurposing of useful waste material wasn’t unknown to Soviet chess factories, as discussed in my chessays on the Kyrgyz kyyal’s of Central Asia. But to hammer and sickle my hunch home, here’s how a Kombinat is defined in The Great Soviet Encyclopedia (3rd ed. Moscow, 1969-78), “COMBINE: specialized industrial and cultural goods factories sequentially processing or making comprehensive use of raw materials, scrap and by-products.” But we’ll leave that train of thought at the station for now – as we have another steam engine to catch!

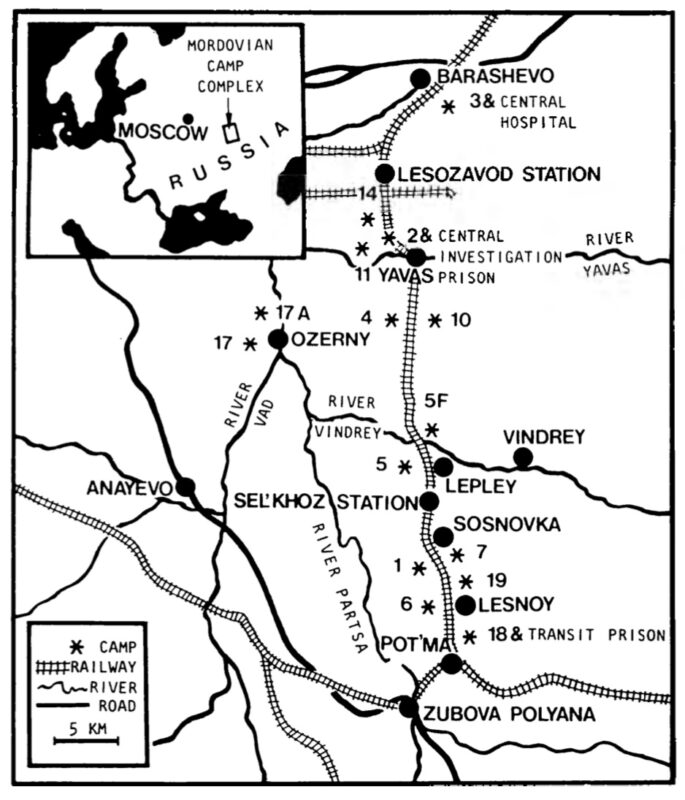

After a bone-numbing overnight stay on a dank prison floor, Horst was herded onto the rattling old railway cars called ‘stolleys’ (first used under PM Pytor Stolypin, i.e. before 1911) that journeyed up and down the 35-mile stretch of track that formed the backbone of the Temnikov Industrial Combine. The Tsarist-era engine would steam right through the heart of the Temlag labour camps until its last port of call at Barashavo, stopping only at the various prisoner transit points to fertilize the Gulag along the way – and what a fearsome first impression that journey must have made on the farm-boy from Krussau!

Departing at dawn from Potma the crammed carriages would have wound their way north through the dense deciduous forests of the Zubovo-Polyansky Oblast, riding the undulating spine of the monster that was the Temlag. They would have first seen the textile and lumber camps of Lesnoi (Gulag No.1, 6 & 19) – lesnoi literally means ‘forest’ in Russian – then travelled on past the old sawmills and iron foundry at Sosnovka (Camp No.7), remnants of Lenin’s first Five Year Plan. Then following a prisoner drop at Selkhoz (Transit Station No.9) the expansive Cultural and Household Goods Plant at Lepley (Factory No.5) would have come into view. And here we’re going to jump the train and stretch our legs for a moment, as we know for a fact that the brow-beaten carpentry brigades of Lepley’s Factory No.5 were churning out ‘Mordovian’ chess pieces in their tens of thousands from the mid-1940s until the 1960s when Khrushchev’s Thaw froze Gulag production across the entire USSR.

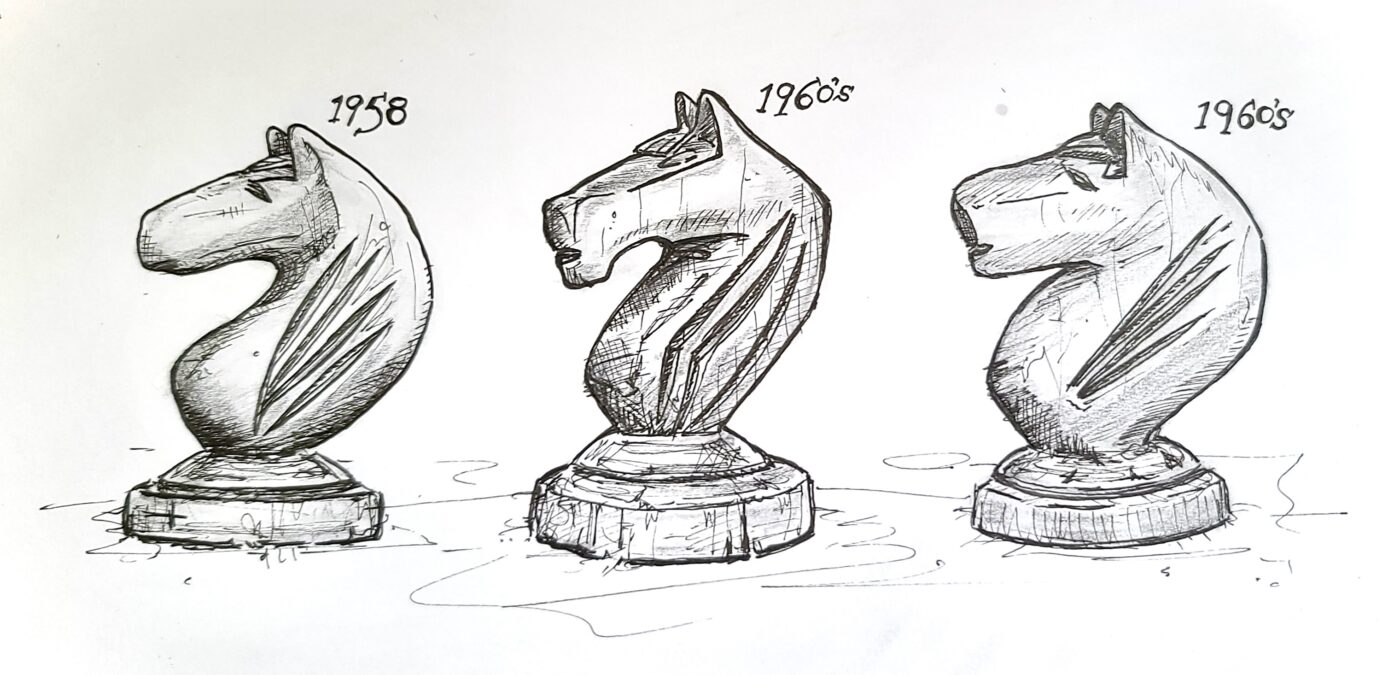

To use a familiar Poratism, a ‘quintessentially’ Mordovian F5 (or Factory No.5) chess set can be viewed at the Moscow Chess Museum. Manufactured, as the exhibit label dramatically states, “in the cold summer of 1953” (chilled by Stalin’s demise, no doubt). The curvaceous cut of the knight and the intricately carved wing-bars make this pattern particularly easy on the eye. Here’s the museum set candidly photographed in 2019 by chess historian and author, Doug Griffin (@dgriffinchess). This is the larger, tournament version of Horst Hennig’s set.

All the Mordovian F5 sets were accompanied by a folding wooden board (and not the one on display!) bearing the manufacturing details on its inners. On the earliest boards (1947-1952) the stamps show the ‘Gulag Star’ (or the MVD’s ‘Made in Gulag’ production mark registered in February 1939) straddling the ‘5-TEM’ of Temnikov Factory No.5 with the date to the left and the category (in most cases, “First Grade”) underneath. To the right of the MVD Star (or ‘Zvedza’ in Russian) is the small triangular OTK-5 stamp of Lepley’s Technical Control Division (Otdel Tekhnicheskiy Kontrolya). These early stamps (or “passes” as the OTK “quality inspectors” called them) are shown below in chronological order, corresponding with sketches and photos of the 1947-1952 knight patterns. To my knowledge, these were the first four patterns produced by the Mordovian carpentry brigades. A more in-depth discussion on the Gulag Star and the earlier Berezovsky Gulag sets (a forerunner of the Temlag patterns) is the subject of the SCS chessay, ‘Children of the Gulag: The Berezovsky Chessmen.’

And now things get a tad involved. Following Stalin’s unexpected demise in March 1953, the Gulag Star disappeared from the stamps altogether and was temporarily replaced (from April ‘53 until March ‘54) with the pragmatic ‘Tempromkombinat Zavot No.5’ (Temnikov Industrial Combine, Factory No.5). This coincides with the termination of the MVD’s control of the Gulag system, which we’ll touch on shortly. Some examples of these stamps are shown below.

The sleek design of the classic 1953 knight is particularly attractive, and in various guises gallops on well into the 1980s. The Soviet Combines had this annoying habit of achieving perfection and then slowly destroying it via means of over-simplification to ramp up production – a dilemma succinctly captured in this 1974 illustration from the satirical Soviet mag, Krokodil. The quippy caption reads, “We’re in time trouble – sac the quality!” The lampoonist, Zharikov, portrays an OTK Chief Inspector holding a First Grade (‘Copt 1’) stamp in hand, hastily approving what appears to be a beltline of caricatured Mordovian chess sets on their warped folding boards. How delightfully topical!2

Cackles aside, here are some nonfictitious Mordovian examples spanning the years 1953-1958. Quite clearly, the original 1947 F5 knight carries the greatest influence on later variations and sets the standard for what is easily the most ubiquitous of all the Gulag patterns.

The Soviet leadership crisis of 1953-54 marked a period of upheaval and uncertainty for the MVD hierarchy that governed the Temnikov Combine. Under Stalin’s replacement, First Deputy Chairman Lavrentiy Beria, control of the Gulag system was transferred from the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the Ministry of Justice and a calamitous mass release of millions of prisoners (leading to an unprecedented crime epidemic) prompted a coup d’etat by Nikita Khrushchev (Beria was executed in December). In short, First Secretary Khrushchev “reimagined and reformed” and eventually “dismantled” (by January 1960) the entire Gulag system, but in the remote forestscape of Mordovia, it was business as usual. The lathes of the carpentry brigades never stopped spinning, they just turned for a different master.

In March 1954 the abbreviations 5-TEM and Tempromkombinat disappeared forever from the Mordovian stamps and the ‘Star’ trademark fell under the control of the OTK who incorporated the emblem into their own rebranded triangular stamp (shown above). During this period of reformation and distancing from the MVD – and for the entirety of 1954, in fact – the Industrial Combine remained “officially nameless” known only by the code KI-314 (or, ‘Location 314’) seen top right of the stamp. These 1954 sets seem to be quite rare, probably due to the upheaval. Here are two medium-sized, First Grade sets from that year. Many of these smaller sets were made in the training camps and bear a close resemblance (both in size and their overly lacquered appearance) to Horst Hennig’s 1952 chess set.

During Nikita’s hasty Thaw of ‘54 and the gradual de-Stalinization of the Gulag system, the “soft” Special Camps established in 1948 for politicals and juvies, the “normal” criminal Temlag Camps and the “back-breaking” Temnikovsky Industrial Camps were wrestled from the clutches of the MVD and united under one red banner, the Dubrovnyi Corrective Labour Camp (ITL ZhKh-385) or Dubravlag (Rus: “The Oak Works”). During the Dubravlag years, from 1955 into the early sixties, the stamps consistently carry the numerals “385/5” – the last three digits of the ITL code and ‘/5’ indicating the set had cleared inspection at OTK Factory No.5.

Intriguingly, after the original 20-year-old NKVD trademark for the Gulag Star finally expired (at midnight on February 15th 1959, to be nerdishously precise) the OTK adopted a simplified version of the five-pointed Star, as seen in the lower right stamp from 1959. Following even more upheavals and reshufflings during the ‘60s, in 1967 the rebranded OTK, and its subdivision The Ministry of Cultural and Homemade Goods adopted an artful twist of the Gulag Star, a subtle play on the initial ‘K’ (or Kachestvo, meaning ‘Quality’) rotated inside of a star-shaped pentagonal shield. But here I go leaping ahead of our chronology by ten years or so. So let’s back up the locomotive and rejoin our stolley stationed at Factory No.5

Jumping back aboard The Temlag Express we rejoin Horst Hennig as we clatter our way over the River Vindrey, passing the woodworking and lumber processing camps (Gulag No.4 & 10) on towards our next drop-off point, the Yavas Central Prison and Industrial Combines (Gulags 11, 2 & 14), the first of which, the older and wiser Prisoner 2-348 would be released from in just a few years – if only he knew! After crossing the Yavas River, the youngster would only be eight miles away from his final destination, “die Jugendstraflager,” as he called the Juvenile Colony at Barashavo – the ‘achsel’ of Yavas – where he’d quickly gain an understanding of just what it took to stay alive in Special Camp No.3.

BARASHAVO, GULAG No.3 (ZhKh-385/3) / Juvenile Corrective & Educational Camp, April 1951

In order to survive the dog-eat-dog world of the juvie, the young German adapted to his new environment quick sharp. He immersed himself in what Solzhenitsyn calls “the language of the Archipelago” – the vulgar Russian slang of the thieves. He got “in tight” with a Russian companionship of criminals, a kind of mini-mafia, became a ‘knight’ and swore the oath of the blatnye – the “thieves-in-law” of the Gulag. After “six to eight weeks,” Horst tells us, “…the gang became my family, my language became theirs, my behavior was their behavior, and if the gang leader told me to cut off some son-of-a-bitch’s ear, I would do it. Feelings no longer existed in me. I was emotionally cold. Pitiless. Only within the blatnye I felt safe. We did everything as one; ate, walked, slept. That was my family; the gang leader, my father.” Eerily echoing Stolzhenitsyn’s description of the camp juveniles, “…they accepted the Archipelago with the divine impressionability of childhood. And in a few days became beasts there. And the worst kind of beasts, with no ethical concepts whatever.”

Surviving on his gut instincts and cunning alone, Horst protected himself from the everyday violence of “Barashevlag” (Special Camp No.3) by siding with the gangs of thugs, the beasts who ran the juvie by dishing out the violence themselves! Then in late summer, as he vividly recounts in the Contemporary Witnesses interview; “… I was told of an opportunity where I could apply for training as a ‘tischler’ to learn the general carpentry work (tischlerarbeiten) while I was still a teenager. And so I met there [at the woodworkers camp] with the brigade’s ‘bandenfuhrer’ (gang leader), an older Russian named Kolya, and we came to an understanding. I said if I go to the ‘arbeitslager’ and have to work, maybe I don’t have to work too much? And he says, you don’t have to work at all in the labour camp! We don’t work there either, and nor do any of our people [the blatnye]. And so I said I liked the idea and myself and a ‘kamerad’ volunteered (‘freiwillig’) to do the training with the carpenters there.”

What he doesn’t say is “and that’s where I made my chess set.” Which would have been nice. Horst does tell us, however, that in March 1952 he turned eighteen-years-old3 and around three months later was transferred to “Lager Sieben,” one of the adult woodworking camps for ‘politicals’ that we’ll visit shortly. So, here’s where it stands: if we compress the Madrid exhibit info into a nutshell, it reads; ‘A chess set made in a Soviet youth prison in 1952,’ meaning he must have served most of his training (roughly between late August ‘51 until June ‘52) making chess sets, boards, and what not with Kolya and his carpentry brigade.

Exactly where Hennig stood on the production line (as it’s very unlikely he “made” the set all by himself – especially if he was allergic to work!) is inconsequential. Mind you, if you have a medium-sized 1952 Mordovian F5 set, who knows? Maybe Horst worked on it! What is of paramount importance here is Hennig’s first-hand account that chess sets were being carved and turned in different sections of the labour camp and not exclusively at Ledley’s Factory No.5. And just think of it. The number of individual chess pieces produced by the Gulag in the ‘50s runs into the tens of thousands – incalculable, astronomical numbers! Therefore, it seems highly likely that they were manufactured throughout the Temlag by different woodworking brigades. A theory reinforced by a Dubravlag official document recently unearthed by the collector and historian, Sergey Kovalenko, which plainly states that “Promkombinat Gulags Nos. 4, 5, 7 & 11” were “woodworking and furniture” plants that spanned the entire spine of Dubravlag. A theory that could also explain why there are so many Moldovian variations; as different carpentry brigades in different sections of the camp may have specialized in differing patterns – but that’s a subject too vast for this chronology.

SOSNOVSKA, GULAG No.7 (ZHKH-385/7) / Wood and Metal works, June 1952

In late June after completing his introduction to woodworking in juvvy, the prison-hardened young German, Horst-Adolf Hennig, was transferred to work with the adult carpentry brigades at Sosnovka (Camp No.7), situated just three miles away from Ledley – in spitting distance, you might say! “At Lager Sieben,” he enthused, “…they had everything, a Radio Factory (“eine Radiogehausefabrik”), a Sawmill (“Sagewerk”), everything was there” – unfortunately including prison gangs. And he didn’t get off to a flying start! The Sosnovska sawmill (a timber processing plant that turned logs into lumber and lumber into furniture, toys and most probably chess sets) was run by “a bunch of Germans …” as Horst, the ‘fresh-meat’ recalled, “…that I spoke to in my way, the way I learned” (meaning the language of the thieves). Horst was then taught another lesson – a painful one. Later, as he was licking his wounds, one of the carpenters, “ein Deutscher kamerad,” took him quietly aside and said, “If you want to survive here with us Germans, my friend, firstly, talk to us properly. Lose the filthy Russian slang. Use it here and you won’t get along that well.” I bring this episode to our attention, because these German carpentry gangs running the sawmill were most probably very skilled woodworkers, as is evident in many turn-of-the-century German chess sets, as can be seen here in Holger Langer’s recent book, On the Collecting of Chess Sets, and were an unquestionable influence on post-WWII Soviet sets.

We can’t say for certain that any chess sets were manufactured at Camp No.7 (Horst makes no mention of the type of work he did there), but we do know it produced furniture and other cultural goods – which generally included chess sets. If we eventually discover it did, well, that wouldn’t surprise me in the slightest; first of all, because of its close proximity to Factory No.5; secondly, because he was schooled at Camp No.3 to make chess pieces; and lastly, because of the sheer volume of sets produced by the various camp carpentry-brigades over the course of the 1950s, as discussed earlier.

YAVAS INDUSTRIAL VILLAGE, GULAG No.11 (ZHKH-385/11) / Wood & Metal & Clothing, June 1952

Horst spent two years and change at the Sosnovska wood plant before he was transferred in October ‘54 to the bleak, frigid, unwelcoming northerly industrial complex at Yavas, housing men, women and “dangerous criminals” spread out over three camps. Fortunately for Horst, however, his luck was in for once as he evaded the harsh labour camps of Yavas thanks to Khrushchev’s Thaw. And after serving only four years of his twenty-five year sentence his case was reviewed by the newly named KGB, and taking into account his age and the triviality of his crime, Horst-Adolf Hennig was released from the Central Investigation Prison at Camp No.11 in the spring of 1955.

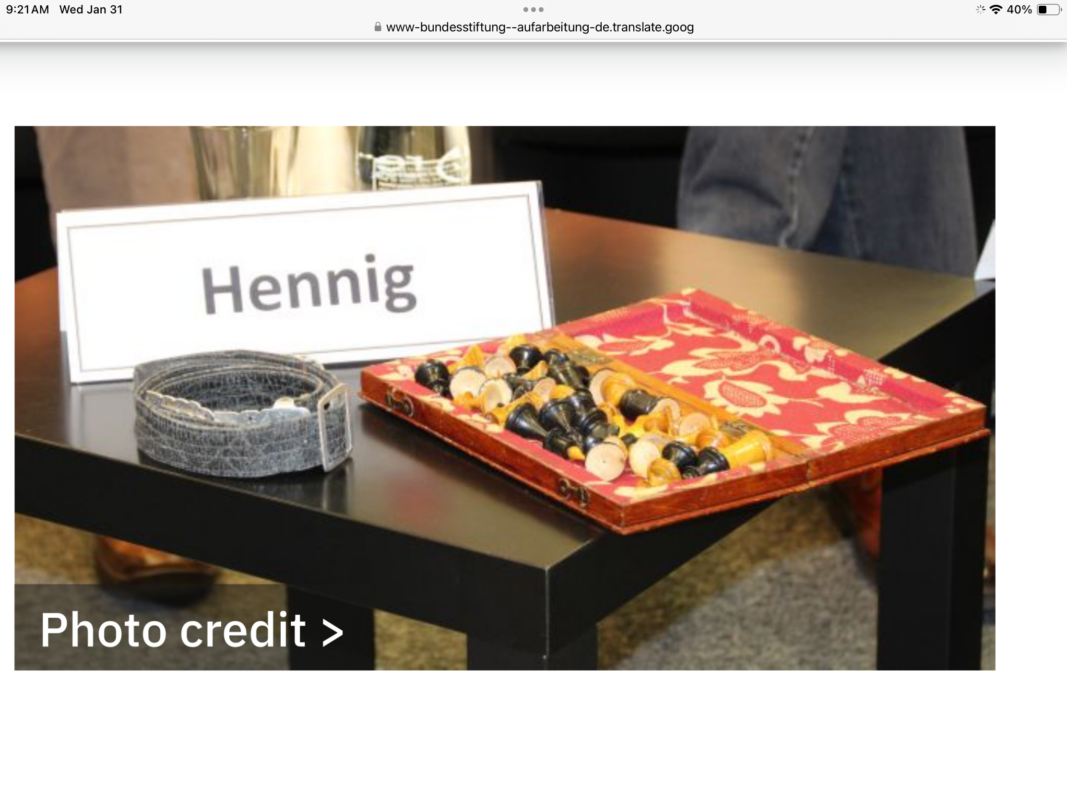

As a twenty-one-year-old adult, Horst Hennig exited the Gulag carrying only three items with him. His release slip, a chess set he worked on in juvvy and a belt made from “crushed tin bowls and old toothbrush stems.” Horst ends the Contemporary Witnesses interview with a reticent, almost embarrassing chuckle explaining that the belt (shown to the left of the set) was a parting gift from my “kriminellen freunden im Lager … that for some reason I’ve kept with me all of this time.” He doesn’t, however, mention the chess set, or whether he made it himself or not. Which would have been nice!

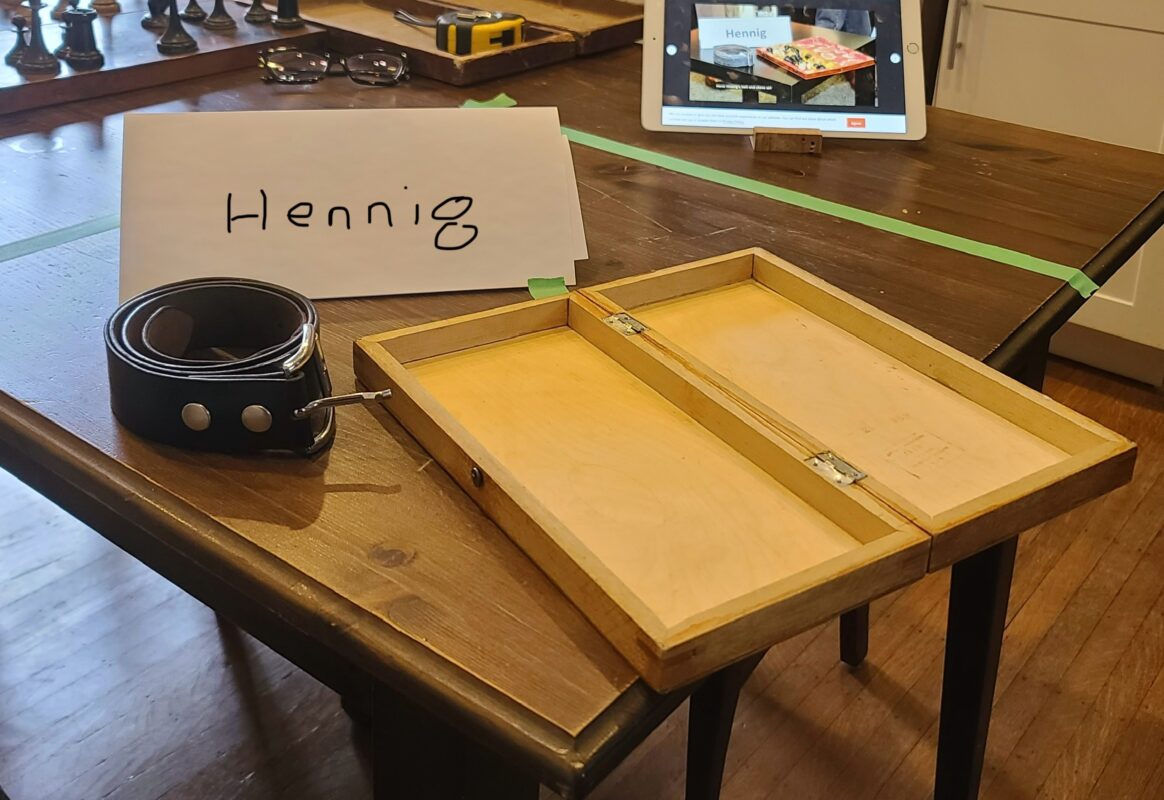

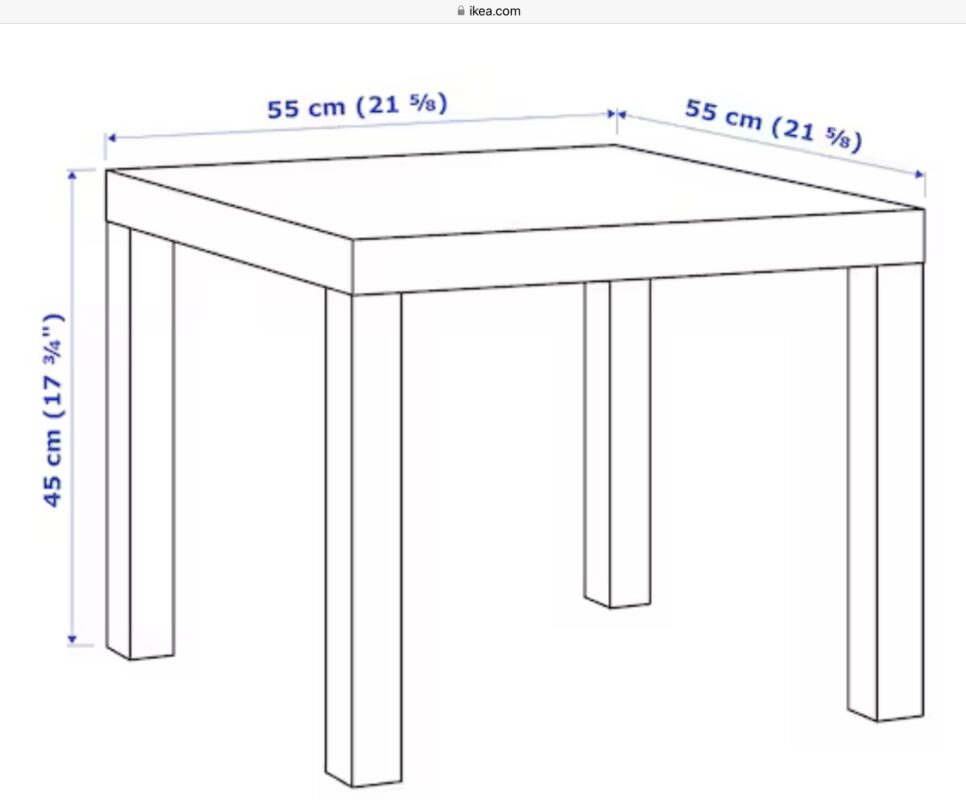

Hennig’s folding board appears to be the same size as one I have in my collection. The squares would measure 1 ¼ inches and the board is 29cm x 29cm. The table it sits on looks very much like a standard IKEA side table (judging by the feet and shins of folk in the background) measuring 55cm x 55cm. Call me quirky, turkeys, but I just had to stage this re-enactment to be sure I wasn’t imagining things (the green tape marks the size of the IKEA table).

I’ll leave the parting words to the Spanish chess collector, Jose Manual Astilleros Garcia-Monge, who kindly provided the following information following his trip to the exhibition:

“I didn’t have time to study the pieces in detail but the first thing that struck me about the set is the excellent workmanship. Therefore, I deduced that the set must have been made in a workshop with suitable woodworking tools, such as lathes. Anyway, it is striking that the set was made by a teenager. The pieces are somewhat small in size, perhaps suitable for playing on a board with 1.5 or 1.75 inch squares. The pieces are very well preserved and I don’t know if they have been restored or not. Finally, I just want to show my deepest admiration for all those people who in such difficult circumstances are able to produce such works of art”.

Fine parting words. Until next time. Check you later, Schachers.

Enjoy your chess and enjoy your Mordovian F5s!

All rights reserved, Alan W. Power, The Chess Schach, February 2024.

Special thank you to Sergey Kovalenko for his research assistance, John Moyes for his help with translation, Maksym (Etsy shop @MaximusByMax) for sharing his photo catalogue, Mykhailo Kovalenko for his encyclopedic knowledge of dates and all those collectors who continuously share their vast knowledge on Shakhmatnyye Kollektsionery. And my amazing and gorgeous wife who makes this all appear online as if by magic.

CREDITS

LEADER: Chess Schach

PIC 1; (Shakhmatnyye Kollektsionery [SK] fb page, Jan. 26) photo: Jose Garcia-Monge.

PIC 2: solitary cell, Wiki

PIC 3: LEADER: Temlag, photogulag.perm.org

PIC 4: blue cloth bases, ‘50s Mordovian knights, CS

PIC 5: Gulag map (Wiki)

PIC 6: 1953 Moscow Museum Set; Douglas Griffin

PICS 7-16, CS, SK and SCS and Mykhailo Kovalenko

PIC 17: Krokodil 1974. Source; Sarah Beth Cohen

PIC 18-23; CS, SCS, MaximusByMax Etsy Store, ChessUSSR Etsy Store

PIC 24-32; CS, SCS, MaximusByMax Etsy Store, ChessUSSR Etsy Store

PIC 33-37; CS, MaximusByMax Etsy Store, ChessUSSR Etsy Store

PIC 38-41: Jose Garcia-Monge, CS, gulag archive (bundesstiftung-aufarbeitung-de)

QUOTES:

The German notes to Hennig’s interview can be found here: Gulag Contemporary Witnesses Podcast; gulag archive (bundesstiftung-aufarbeitung-de)

Between 1950 and Stalin’s death in 1953 the Gulag population hit its peak with an average of 2,500,000 people in prison camps throughout the USSR. stats:gulaghistory.org

Sentenced to a tenner or a quarter “for taking a stalk of grain, a cucumber, a chip of wood or a spool of thread.” GA p.35

the old sawmills and iron foundry at Sosnovka (Camp No.7), remnants of the Lenin’s first Five Year Plan. The Natural and Cultural Heritage of Mordovia; Chronology. tourismportal.net

These early stamps (or “passes” as the Soviet “quality inspectors” called them); Quality Control in Soviet Industry 1948-1954 (CIA document on the OTK, Feb 1955) www.cia.gov > readingroom > docs

BIBLIOGRAPHY & REF. WORKS

The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksanor Solzhenitsyn (Paris, 1974).

The Gulag after Stalin, 1953-1964. Jeffrey Hardy Cornwell Uni. Press 2016

Khrushchev’s Gulag: The Soviet Penitentiary System after Stalin’s Death, 1953-1964. Marc Ellie, Toronto Uni. Press, 2013 (hal.science.com)

Mordovian Polital Camps: Dubravlag (museum.khph.org)

- 1

Gulag – Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei: Main Camp Administration

Temlag – Temnikovsky Corrective Labour Camp (1931-1954)

TEM – Temnikov Industrial Combine, (1948-1954)

DUB – Dubravnyi ‘Special’ Camps (1948-1954)

Dubravlag – Dubravnyi Corrective Labour Camp, ITL ZhZk-385 (1955-2005)

ZhKh – Communal Housing Institution: Zhylishchno-kommunalnoe Khoziaistvo

ITL – Corrective Labour Camps – Ispravitel Trudovoy Lagerei

OTK – Technical Control Division: Otdel Tekhnicheskiy Kontrolya

NKVD, MVD, KGB – Ministry of Internal Affairs

KgU – Fighting Group against Inhumanity

CS – The Chess Schach: thechessschach.com

SCS – sovietchesssets.com

↩︎ - Chuck Grau wrote in SK (Feb 22, 2024) “reposted from Sarah Beth Cohen. It’s the end of the fiscal quarter and our Master Technical Controller is speeding up production to meet his [quarterly] quota. Of course, as he’s paying attention to the calendar, he’s disregarding his work, whose quality is suffering accordingly, even though he continues to stamp the sets “First Sort” or highest quality. In the caption he rationalizes the crappy quality by telling us that quality sacrifices must be made under time pressure.” [SK member] Alexcy Spectre also explains, “it’s a pun – ‘quality sacrifice’ [in Russia] is what’s known as ‘exchange sacrifice’ in English.” ↩︎

- Hennig, perhaps understandably, wasn’t great at pinpointing exact dates in his interview with Stark, so from his birth month and other dates (like Xmas, late summer, etc) I managed to piece together what I believe to be a fairly accurate chronology of the years in question. ↩︎

Excellent research and a compelling story!